Who or what is killing Jazz and why?

By Al Calloway

Academically speaking, the music popularly called jazz is American classical music. So-called jazz music was created by descendants of Alkebu-lan -- the continent called Africa by Europeans -- who survived the horrible Middle Passage and the slave-driven plantocracy created by the Trans-Atlantic African Slave Trade.

These survivors, though devoid of their native cultural expressions, yet developed spirituals, work songs and, later, gospel music and the blues, all of which begot so-called jazz. The quintessential American musical art form known as jazz is recognized all over planet Earth. However, almost imperceptibly, the art form is being bulldozed into oblivion in the United States of America.

Remnants of this great music can be found in a few small clubs, mainly in New York City, Washington, D.C., Chicago, St. Louis, New Orleans, and Memphis and on the West Coast. Suburban clubs especially prefer white musicians who can at least play the genre. Renowned black jazz musicians mostly work abroad, in Europe and the Far East. Many who stay in the U. S. A. have to swallow their pride and play the desired fusion, elevator music and rhythm and blues, in order to eat regularly.

And female jazz musicians fare even worse. Back in the day, the music of women, including singer/pianist Nellie Lutcher, song stylist Savannah Churchill, Mary Lou Williams, Hazel Scott and Dorothy Donegan, was the rage before Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn and Carmen McRae took the music to a new level.

They prepared the way for Betty Carter and Abbey Lincoln much like Bird, Dizzy and Monk begot Miles, ’Trane and Cecil Taylor. And there’s a new cadre of great female jazz musicians whose voices we cannot allow to be ignored, sisters such as Esperanza Spaulding, the Grammy winner jazz bassist/singer who performed for President Obama at the White House. There’s pianist Geri Allen, drummer Teri Lynn Carrington, violinists Karen Briggs and Regina Carter, guitarist Monette Sudler and on and on.

The countervailing forces against African-American accomplishments, including jazz, are historical, political, cultural and market-driven, all by a white nationalist mindset. Africans were brought to the Western Hemisphere to serve white people as slaves and servants. A huge percentage of Eurocentric minds can conceive of waging war to preserve that – which, for them, is an historical reality. (Never mind the immoral legacy of that historical act.)

Across the board politically, whether liberal, independent or conservative, in the main, white nationalism is the sine qua non through which and whereby America is to be run, perpetually. Therefore, the cultural appurtenances that accompany being white inexorably include defining anything “African American” or black as debased.

Finally, through the market economy, political and cultural control is meted out. Promote tattooed, bling-bling-wearing blacks with pants on the ground, spewing anger, threats and malice with prostitute-looking females and sell it everywhere as music and style; make billions of dollars while reinforcing negative stereotypes of black people.

One last thing, lest we forget. In the final analysis, we, the African people throughout the Diaspora, are responsible for that which is ours. American classical music, so-called jazz, is our gift to the world. Therefore, we must protect and perpetuate that which is ours. We must even protest loudly when and wherever the name “jazz” is used to promote a venue that is actually a rhythm and blues or reggae concert.

Let us also remember that cultural means the following: “of or relating to the cultivation of the mind or manners, esp. through artistic or intellectual activity.” (from the Oxford American Dictionary.)

South Florida residents, visitors and friends have a rare opportunity to support “Women in Jazz South Florida” on Saturday evening, May 14, at ArtServe, 1350 East Sunrise Blvd., Fort Lauderdale. Go to www.wijsf.com for more information.

Al Calloway may be reached at Al_Calloway@Verizon.net

![]()

Response from Dinizulu Gene Tinnie:

Al's article is so to-the-point. My reply typically dances around a few points in the quest for coherence, but, for what it is worth.

Asante sana, Joan,

Quite a dialogue you have been having with Ahmed. It brings to mind that classic line from Stevie Wonder: "We're all amazed but not amused by some of the things you say that you do..."

It's crazy that at this point in time (we keep believing that we should be progressing, if not evolving), we still have to be arguing about the politics and economics of the music called "jazz" (a.k.a. African American Classical Music). It's crazy, but for that very reason it is not surprising, that it still goes on, just like the rest of the insanity. And that is probably the main point: Jazz is the shining tip of the iceberg, and its mistreatment, misrepresentation, misunderstanding, abuse, exploitation, and downright misappropriation and misattribution by others are but symptoms and symbols of the larger psychosis, which is the disrespect for life, nature, humanity, and God that we have endured for at least the last five centuries in the form of the "slave trade" (the Middle Passage), slavery itself, colonialism, and, now, neo-colonialism and neo-slavery in neo-legalized forms like IMF/World Bank parasitical control of African World national economies, and, here at home, such institutions as sharecropping and, most of all, the prison industry. The irony, often bitter, of course, of all of this suffering and injustice is that it has so much to do with the creation of the music itself.

The Swedish playwright Par Lagerqvist (sometimes we just give thanks for those flukes of circumstance that bring us in contact with these otherwise hidden gems) wrote an extraordinary play entitled "The Hangman." It plays on that familiar theme of that evil presence that is always around to witness, aid, and abet humans at our worst. The play contains a memorable scene in a night club with all white patrons listening to an all-Black jazz band. The band comes to the end of their first set and prepares to take a break, but just at that moment, a drunken patron, who had left the room returns, and demands to know why the band has stopped playing. The musicians try to explain, politely, that they have been playing, they are hungry, they are taking a break, and will return. That is not enough, and the drunk escalates the coinfrontation until it becomes an all-out physical brawl. In the brawl, one of the players is shot dead. (The Hangman, sitting in the back of the room, looks on; his work is done.) The drunk and his fellow patrons order the musicians back onto the stage and command them to play. This they do, over the corpse of their fallen comrade. As they play, the white audience is just enraptured by the music. "I knew they were good, but I never heard them this good!," and such sentiments.

You get the point. That night club audience will go home satisfied that they were blessed with an extraordinary performance of the world's greatest music, and the musicians go home, well, in that way that musicians always go home, only worse, after having delivered their best. (Having READ the play, I wonder if it has ever been actually presented anywhere; getting a cast of musicians to play the role would be a challenge to say the least, but quite a performance indeed, if it were ever done.)

At the risk of belaboring the point, I will share another example, which i may have shared with you before, from our good friend Dr. Al Pinkston, who had returned to Florida Memorial University, where he could boast of having recruited quite a number of music majors, and, even more impressively, students interested in learning and playing jazz. As he shared the story with me, he told me of how many students, when he made the offer to them, did not hesitate to say, "Dr, Pinkston, I don't know anything about jazz." He would counter that assertion with this reply: "

Oh, you know about jazz. let me tell you a story that my grandmother told me. There is a Black man, let's call him Willie, sitting out in front of his house on a Saturday morning, whittling a piece of wood. White man comes along

"Morning, Willie"

'Morning, Mr. John."

"I'm, going in to see Sally now."

"Yes, sir, Mr. John," and Willie keeps on whittling.

When the white man is finished, he takes his leave, saying, "OK, Willie, I'll see you next Saturday."

"Yes sir, Mr. John." Willie is still whitling the piece of wood, but now he starts humming.

That humming? That's jazz! So don't say you don't know anything about jazz.

(A sidebar on the humming phenomenon in African American culture. I never thought of it until I heard this story. If you read Maya Angelou's "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings," you may recall the scene in which some poor and dirty white children insult young Maya's grandmother by stopping in front of her house, and one of the girls does a handstand, allowing her dress to expose her legs and unclothed genitalia to the view of grandmother and granddaughter. The older response of the older woman, who is deeply religious, is simply to hum. Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison's last[?] novel, entitled "Love," as I recall, opens with a scene where young women are sitting with their legs ungraciously open, to which the main character responds by humming. And then there is even the speculation that English slave ship captain-turned-preacher John Newton might have got the melody for his most famous composition. "Amazing Grace," from the humming of the Africans chained below in the storm tossed ship he commanded when he vowed to God that if he were saved from this calamity, he would pursue slaving no more and serve the Lord forever more. Somewhere in there seems to be a rich vein to be mined by cultural scholars and behavioral scientists alike.)

These examples serve to confirm your point that "jazz" (AACM) is truly a uniquely African American production and idiom, "born of heart and soul aflame," as Len Pace used to recite on the air, and rooted in the unique circumstances and cultural traditions of African peoples in the United States. It is, in fact, as has often been pointed out, America's only truly original contribution to world culture. This is undeniable, and stands as its own proof. Yet, others have purloined the language of jazz, its outward forms, its grammatical structures, so to speak, and have not only toot-tooted their way to fame and fortune in pale imitation of the true article (which may be too strong a dose of truth for some), but have gone so far as to (mis)appropriate it and to declare themselves to be the genuine practitioners of what, a supposedly crude Negro language that they have cleaned up? The insane irony of Paul Whiteman being proclaimed as "The Father of Jazz" doesn't really need any further comment here, but his large portrait, with that appellation, still stands at Williams College in Massachusetts, where no one, as far as I know, has seen fit to retire it to an unseen storeroom of curious relics which the institution might claim the distinction of owning.

The point that I am getting to, in a very roundabout way, which I must continue briefly, is the same one that I mad about Black visual art in a panel discussion during Art Basel | Miami this past year, and only yesterday regarding Black business and community development to an earnest group in north Florida with whom I have been in correspondence. To digress (again), one of the most frustrating experiences for the person who does research is to find that gem of a quotation that seems to answer nearly al questions, and then forget to make note of the reference (page no., source, etc.) Such was the case with a classic History of Slavery, from Biblical Times to the Present (that might be the exact title) by W.O. Blake published in 1848 (or thereabouts). Somewhere in that massive tome, as I recall, the author makes a profound statement to the effect that a point came in history, as trade and exploration began to establish a new global order, when all of the earth's other peoples, colonizers and colonized alike, recognized that the African would be the thing at the bottom of the pile, to be exploited by all. The African will be the human who is not human, who has no proprietary tight to his/her land, resources, labor, or skills, and most certainly not to anything like what we call today "intellectual property." That unwritten global understanding (which had its exceptions, to be sure, like the Native Americans, and even that was limited) has been the foundation of the global geopolitical order and system we live in today.

In the art world, for example, it is well understood that the price to be paid for, say, a traditional carved mask to the African artist, if there is a price at all (outright theft, sometimes justified by a veneer of religious justification by missionaries or by other such ploys, has been equally effective as a means of acquisition), must be a low price indeed. One purchased, however, not only does the price at the gallery owned by the European collector skyrocket, but it is the collector who earns the praise for the brilliance of his/her collection -- what skill, and courage, it must take to venture into those places and to have an eye for such magnificent pieces! And the collectors, dealers, critics, and scholars will hold forth in verbose rhetoric on what these pieces mean in their original setting, without once asking an African for an opinion.

In the business world, where greed and rapacity are accepted as the normal rules of the game, the stories are legion of "venture capitalists," who provide Black innovators with just enough capital to get the business going, but. just when it starts to get successful, there is a shortage of funds, and the "solution" becomes ownership by others while the original innovator is lucky to hold on to a management position. Of course, this is considered "progress" in some circles, compared to the days of slavery when Black skills, expertise, and knowledge were simply the property of the "slave's" owner, to be rented out for his/her profit. Shouldn't we be glad to be living in such a place? (This is not to deny the many success stories that there are, but those many are still too few. We can celebrate that there are Black CEO's of major, Fortune 500 corporations, getting paid well, but how many of those corporations have Black Board Chairs, or Black majority ownership of stock shares? Being hired help is not the same as owning.)

I am not trying to paint to bleak or pessimistic a picture, but I am saying that the conversation that you are having with Ahmed is against the backdrop of this entrenched, cultural, social, political, and, if need be, military reality, which is the world as we know it today. Not only does the odious doctrine of capitalism, historically linked inextricably to the agenda of White Supremacy, rule the economy of practically every nation, at least financially, but we also don't have to look very far to see that the most successful people in the world today (at least materially) are also those who are thoroughly without morals. Has it always been thus? One would have a hard time even imagining a traditional African, Native American, or Aboriginal society that would tolerate any such behavior. We come from societies where a person's status is based on what (s)he gives, rather than takes, on what is shared, rather than what is claimed to be exclusively owned. Individual, or even collective greed had no place, least of all as a motive for producing music or art, which occupy a special place in society, which is so thoroughly integrated into the rest of life that many African languages do not even have a separate word for "art" or "music."

Clearly, the same is true of the origins of the music we now call African American Classical Music, or "Jazz." Here is a product of African American genius, evolved from "field hollers," and coded-language spirituals, and country blues transported into urban streetscapes, a universal language of truth that is appreciated by audiences all around the world, but the entrenched culture of global prejudices that have even persisted after decolonization (or, if anything, gotten worse) still dictates that the African American is not the one who should own, control, and be paid for this cultural treasure, which has been reduced, like everything else practically, to a commodity on the world market, for the profit of others. Some parts of the world are enlightened enough to have become havens for musicians, where they actually can get their due respect, and income. But there are still to many places where the thieves and imitators of the music are passed of as the "real" thing (your exchange with Ahmed on the subject of Kenny G. is interesting, and revealing, on this point). There are still to many places where club owners and music publishers get the lion's share of the profits that the music generates, even if the musicians are performing live. And then there is this even more pernicious phenomenon of "digitization." There was a time when a musician could get a gig (I know some who did) as a side (wo)man doing studio work, or producing commercial jingles and the like. Now drummers are "obsolete," because mechanized drum tracks provide all that the industry needs for rhythm and backbeats.

So, should this dire state to which humanity has descended become the new lment that will inspire even more brilliant forms of "jazz," as in the Lagerqvist play? Probably yes and no, for those who have time to ponder the question. Music, after all, is a dynamic thing. It changes, grows, and evolves. Who foresaw the transition from Swing era big bands to Bebop combos, and the whole change in the social function of the music? Now Hip Hop (originated in African America) has become the new voice og the dispossessed, the resistors, the self asserters of their (our) humanity, with its hard-edged aesthetic of not even admitting the kind of vulnerability that makes love hurt and produce deeply truthful ballads. (And yet, true to form, Hip Hop has also been appropriated and controlled by a publishing industry that makes sure that certain messages of urban amorality and "dissing" get more play than the conscious messages that we never get to hear.)

However, with all of the changes and the evolution, jazz is still, like European symphonic music, Flamenco, Hindu ragas, etc., a form of CLASSICAL music. It is an idiom with its traditions, that have become timeless. Global cultural history has made it possible for pretenders to "market" watered-down versions to impressionable audiences who have been cultivated not to think too much, and who often get rewarded with disposable income for their compliant numbness, and therefore an industry has been created. "Soft jazz" has a ready market of light-minded listeners. Would that same market be interested in the real thing? Or, does the "market" for the real thing have the money to support it? Has that not always been the challenge of the creative jazz musician (or revolutionaries everywhere for that matter)?

The way the problem has been solved in those "enlightened" places I mentioned is by democratically elected governments, which support their national pride rather than just corrupt cliques of cronies, subsidizing the culture and making it affordable and accessible to the vast majority of their citizens. This is how Opera stays alive, and art museums, and contemporary art and artists, including jazz musicians, so that these nations can still thrive on and preserve their cultural patrimony, rather than give it up in favor of video games, for example. (Even so, as a result of that, much of the support now goes to their own national musicians who grew up inspired by the African American jazz aesthetic and who have embraced it on their own terms, so that there are still revered African American icons of jazz [mostly male, as you point out], but not the same kinds of opportunities as there once were for Black expats who carry the original Word.)

This, I think, is what brings us to the point of the dialogue with you and Ahmed. The "culture vultures" have so despoiled and pillaged the treasure of jazz that some ersatz version can now be put on the global market and audiences will buy it, thinking it is "jazz." We have that expereince here of going to so-called cultural festivals where folks admire but walk past the original works by artists and walk out with cheaply framed cheap Chinese prints like the Last Supper Scene with Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Frederick Douglass, etc, under their arms as if they just purchased some real art for their homes. Just as the buyers of those products can care less about what toxic fume-laced sweatshop might have produced it -- in other words the human story behind the thing, as a product of human mind, human hand, human life of real people -- so the modern "jazz" audience has been made to be quite uncaring of the deep origins of the music. It is now just background. Ambience for a conversation of a meal of food with equally unknown and uncared-about origins. (I have often likened our role is society -- as those whom "history has forced, obligated, challenged, and blessed to be truth knowers, truth keepers and truth tellers; SOMEBODY has to "keep it real" -- to that of being the ones who, in an elegant steak house restaurant, draw the curtain aside to reveal a view of the slaughterhouse. Like, what did you THINK you were eating?")

Analogies abound. Our role has been likened to that of the canary in the gold mine who warns the miners when the air becomes to poisonous, but, driven by greed and habit, exploited and brutalized, they barely hear or heed the song, or the lack thereof. We are the ones who indeed "know why the caged bird sings," and why there is even a market for cages. (Paul Laurence Dunbar's poem "Sympathy, from which that line comes, almost seems like an analogy for this exchange you are having with Ahjmed.) "We too sing America," to paraphrase another of our iconic poets, whose great manifesto of 1926, "The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain," might have said it all, for all time:

We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn't matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too. The tom-tom cries and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn't matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.

-- Langston Hughes, in The Nation, 1926. ( https://mail.google.com/mail/?hl=en&shva=1#drafts/12fd3953e7cf7b47)

As you see, you got me again with one of these lengthy responses, but all of these gathered up bits, I think, put the dialogue you are having with Ahmed in perspective. What is happening to jazz is a microcosm of what is happening to all real culture worldwide and to life itself in our time, as everything is becoming commodified and production and consumption are becoming "globalized." Jazz is the most salient and obvious example, but this is a symptom, among many other, more quietly kept harbingers of the truly dire state of disconnected consciousness into which we have been lulled, such as the propagation of a genetically modified, corporate owned, non-reproductive food supply, without so much as a by-your-leave on the part of the citizens. Of the global financial crisis nothing more need be said, other than that close examination reveals that these have a way of happening on a cyclical and planned basis. (You can Google "The Bankers Manifesto of 1892"; maybe a hoax or "urban legend", maybe not, but definitely consistent with the facts-on-the ground.) Ahmed's enterprise is a product of the times, and these times are the product of the times which came before, including all of their past (and present) cultural assumptions which have gone unquestioned by those who profit. He is matching the supply he has to the demand he has, and making a living, legally. You are basically saying that the product lacks "truth in advertising": it is NOT real "jazz," from the original source. Something like me selling Perrier water made in America to a market that is buying it. I think the folks in Perrier, France, might have a point in objecting. (Of course, the name "jazz" has never been trademarked, and that in itself raises a hornet's nest of issues, but somewhere therein might lie the embryo of a strategy for the long-term survival of some Truth.)

What I think is the bottom line to this whole issue is what has been the bottom line all along. It may seem to be (and certainly is, on the most practical, survival tip) the ability of musicians to get paid for what they do the same as all other professionals, but. because of who we are , and where we come from, and what we know, and because our task has always been to be a part of the future rather than the past (which is part of us), leading others into the unknown (and then getting ripped off for our knowledge as soon as we get there, whereupon, we move on from that to the future, again), this whole question takes on more, shall we say, cosmic dimensions. (If you know Helene Johnson's Renaissance-era poem "Ode to a Negro in Harlem," she captures something very profound there, although in outward form it -- and the "Negro" -- might seem quite mundane. Indeed, to quote Dunbar again, "We Wear the Mask.") You seem to be making a case for Truth in the marketplace: If "jazz" is to be represented anywhere, including India, then let it be real jazz, from real jazz practitioners, as it was in the past when those real practitioners were the only global emissaries of the idiom.

But I think history has moved us, as a species, to another place, where deeper questions arise out of the darkness in the light of a new century and millennium, and we see more and farther than we did before, and WE know that this thing called jazz is not just a musical style, or even just another form of classical music, but is the song of the human soul, preserved by a global elite of descendants of Middle Passage survivors, whose task it is, like that of the caste of traditional Griots, to tell the Truth, even in a hostile land. This is a music of courage that communicates with the soul and the hear and inspires human beings everywhere, whose natural striving is to be free and to be who they are. That kind of thing cannot be easily commodified and sold for money in the marketplace.

Joan, you know how this goes: I could go on forever, but I won’t. (Life, after all, is a limited-time offer, and that time IS running out... ;-)

Best all ways,

G

![]()

The

State of Jazz Music

By

Melton Shakir Mustafa

[Edited for this post by Joan Cartwright, Blog Manager]

My

experience as a professional musician for over 45 years, qualifies me to

speak about a subject that many ignore or simply are not aware of and, as

a result, neglect to support an Art form (JAZZ) that is uniquely an

African American experience. Of course, many other ethnic groups played a

role in its overall development. Jazz music has been influenced by music

of European composers as a well as Far Eastern harmonies, modes and

rhythms of the world but its foundation lies in the folklore of the blues

and gospel music.

Recognition

of Our Jazz Heritage and its preservation is by far a major concern and

needs to be kept alive. The importance of the contribution of those in the

vanguard, the pioneers of jazz is noted in every aspect, social,

educational, economic and political arenas of life. Yes, jazz is somewhat

of a social reformer that helps people to see eye to eye (literally). Need

I say more? Also, jazz musicians have been on the forefront as Ambassadors

of music in various countries for many years. According to the New

York Times article by Fred Kaplan, “When

Ambassadors Had Rhythm”, Jazz was the popular music of the early

1900’s and afforded much prestige and recognition.

We

are in a new day and time, now, and the popular music of today is

certainly not jazz despite the remnants of sampled jazz in popular music.

This brings me to the state of jazz music and what its future looks

like.

We

have many young musicians in school in

The

question should be - How can we make a difference in our communities to

support the growing number of young musicians coming into their own?

Surely,

they are our future and we must pass the torch. Will they have to find or

make a new way of making a living as a musician or invent some kind of

instrument that creates an automatic audience that pays to hear their

performance?

Will

they need to plant some kind of seed that grows clubs and different kinds

of venues where musicians can perform and enjoy being creative, expressing

the freedom of impromptu and spontaneous thoughts? Maybe people will

figure out how to communicate their jazz thoughts by telepathy. Come on,

let’s get real.

I

submit that, as elders of the art form, teaching the history of jazz and

knowing the importance of its preservation, its heritage as well as recognizing the vanguard and pioneers of the art

form, together with the young lions is a no brainier to keeping the art

form alive. We should be about supporting jazz in the schools with music

education, on a regular basis, with projects that involve students in

every respect.

I’m

convinced that many of the jazz organizations of

We

must continue to recognize and acknowledge the essence of jazz music as an

intuitive art form that can be used to express the inner most feelings of

everyday life. Jazz is an art form that is pure and clean, untouched by

the intoxicants of the world. It is a language that speaks to the soul and

delivers a message of deep thought. It can charm the soul. We should know

that jazz rhythms, melody and harmony can mesmerize and hypnotize.

I’ve been mesmerized on many occasions. Knowing how music can

influence the mind of youths, we have to be cognizant of bad influences

that are designed to tear apart and destroy the very foundations of the

human family.

From

my experience, Jazz has always been a family affair in a close-knit

community, so tight that the feelings of one musician affects the other by

simply looking at the movement of one another, whether it is eye contact

or body movement. So, when the family doesn’t work together, you have

discord and a disruption of the family tie and as a result. Music that has

no true warmth and affection creates a distorted message. We certainly

don’t want to sound like a computer generating complicated patterns that

mesmerize the mind. Where are the warmth, affection and true story of

oppression in that?

To

me, Jazz is unique, born out of the African American experience. Jazz

tells a story similar to the way Broadway musicals tell stories. It’s a

language that speaks freely of life. Jazz music expresses joy, laughter,

hurt, remorse and every emotional disposition that can be felt.

The play in the music is a result of covering up the hurt and shame

that occurred perhaps because of the economic struggle, social struggle,

educational struggle and religious struggle. False representation covered

up the truth. African

Americans made fun out of a lot of things like the way people danced,

talked or just to pass the time away and, clowning around was common.

African Americans had to come up with different ways of having fun. The

music was designed to have fun in many cases. But jazz music in its

metamorphosis told a true story of the blues with deep wounds.

Jazz

is serious music, not just childish play.

It is challenging, music that makes you think rationally and

logically. It is music that bends like a rubber tree, when strong winds of

emotion erupt. That’s a strong message.

It is music for the intellect that is freely expressed. These are

powerful concepts. So, let the music do the talking. If it touches you,

then the message was delivered.

ã 2011 ZAKI Publishing, Inc.

AUTOMATED JAZZ???!**$%

An

Open Letter to the South Florida Jazz Community:

On February 28, 2010, the esteemed Dean of South Florida jazz radio, Len Pace will retire. WLRN has made the decision to replace him with a generic AUTOMATED jazz feed, with Ids inserted to make it seem that it is a local show, when in fact it is not. I feel that this is a very bad decision and I am asking for your help in dealing with this.

The Jazz community in South Florida is at a critical crossroads. Read the whole post and replies here.

February 6, 2010

Thanks for posting this. We all must be aware that the battle is far from won and that the forces of automation and depersonalization will continue to besiege any cultural tradition especially one as rich as American jazz. This is happening all over the country. The musical director of our local NPR station in Pittsburgh, WDUQ confided to me well over a decade ago that she was no longer selecting the music played but that the station had subscribed to a computer program that picked the music. Then they hired a couple DJ's with newscaster-like voices to present the menu on the air. Not only does the warmth disappear from the program but the quality of the musical information also deteriorates. DJ's who are not jazz people often spout erroneous information that they have read from some source with out realizing how ridiculous it sounds to a jazz fan. Also they initiated a policy of playing 3 songs and then back-announcing the artist's name. Not only is this frustrating when one wants to know who is on the recording but when they do he back-announce, they only mention the name of the leader, not the sidemen which any true jazz fan considers as important as the leader. They keep wanting to convince the public that jazz is dead or museum music and we need to use forums like this one to counter their efforts. More later...

Dr. Nelson Harrison

Pittsburgh, PA

Read

the whole post and replies here.

___________________________

August 11, 2009

By TERRY TEACHOUT

New York

In 1987, Congress passed a joint resolution declaring jazz to be “a rare and valuable national treasure.” Nowadays the music of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker and Miles Davis is taught in public schools, heard on TV commercials and performed at prestigious venues such as New York’s Lincoln Center, which even runs its own nightclub, Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola.

Here’s the catch: Nobody’s listening.

No, it’s not quite that bad—but it’s no longer possible for head-in-the-sand types to pretend that the great [African-]American art form is economically healthy or that its future looks anything other than bleak.

Grant Robertson

The bad news came from the National Endowment for the Arts’ latest Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, the fourth to be conducted by the NEA (in participation with the U.S. Census Bureau) since 1982. These are the findings that made jazz musicians sit up and take notice:

• In 2002, the year of the last survey, 10.8% of adult Americans attended at least one jazz performance. In 2008, that figure fell to 7.8%.

• Not only is the audience for jazz shrinking, but it’s growing older—fast. The median age of adults in America who attended a live jazz performance in 2008 was 46. In 1982 it was 29.

• Older people are also much less likely to attend jazz performances today than they were a few years ago. The percentage of Americans between the ages of 45 and 54 who attended a live jazz performance in 2008 was 9.8%. In 2002, it was 13.9%. That’s a 30% drop in attendance.

• Even among college-educated adults, the audience for live jazz has shrunk significantly, to 14.9% in 2008 from 19.4% in 1982.

These numbers indicate that the audience for jazz in America is both aging and shrinking at an alarming rate. What I find no less revealing, though, is that the median age of the jazz audience is now comparable to the ages for attendees of live performances of classical music (49 in 2008 vs. 40 in 1982), opera (48 in 2008 vs. 43 in 1982), nonmusical plays (47 in 2008 vs. 39 in 1982) and ballet (46 in 2008 vs. 37 in 1982). In 1982, by contrast, jazz fans were much younger than their high-culture counterparts.

What does this tell us? I suspect it means, among other things, that the average American now sees jazz as a form of high art. Nor should this come as a surprise to anyone, since most of the jazz musicians that I know feel pretty much the same way. They regard themselves as artists, not entertainers, masters of a musical language that is comparable in seriousness to classical music—and just as off-putting to pop-loving listeners who have no more use for Wynton Marsalis than they do for Felix Mendelssohn.

Jazz has changed greatly since the ’30s, when Louis Armstrong, one of the supreme musical geniuses of the 20th century, was also a pop star, a gravel-voiced crooner who made movies with Bing Crosby and Mae West and whose records sold by the truckload to fans who knew nothing about jazz except that Satchmo played and sang it. As late as the early ’50s, jazz was still for the most part a genuinely popular music, a utilitarian, song-based idiom to which ordinary people could dance if they felt like it. But by the ’60s, it had evolved into a challenging concert music whose complexities repelled many of the same youngsters who were falling hard for rock and soul. Yes, John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme” sold very well for a jazz album in 1965—but most kids preferred “California Girls” and “The Tracks of My Tears,” and still do now that they have kids of their own.

Even if I could, I wouldn’t want to undo the transformation of jazz into a sophisticated art music. But there’s no sense in pretending that it didn’t happen, or that contemporary jazz is capable of appealing to the same kind of mass audience that thrilled to the big bands of the swing era. And it is precisely because jazz is now widely viewed as a high-culture art form that its makers must start to grapple with the same problems of presentation, marketing and audience development as do symphony orchestras, drama companies and art museums—a task that will be made all the more daunting by the fact that jazz is made for the most part by individuals, not established institutions with deep pockets.

No, I don’t know how to get young people to start listening to jazz again. But I do know this: Any symphony orchestra that thinks it can appeal to under-30 listeners by suggesting that they should like Schubert and Stravinsky has already lost the battle. If you’re marketing Schubert and Stravinsky to those listeners, you have no choice but to start from scratch and make the case for the beauty of their music to otherwise intelligent people who simply don’t take it for granted. By the same token, jazz musicians who want to keep their own equally beautiful music alive and well have got to start thinking hard about how to pitch it to young listeners—not next month, not next week, but right now.

—Mr. Teachout, the Journal’s drama critic, writes “Sightings” every other Saturday and blogs about the arts at www.terryteachout.com. Write to him at tteachout@wsj.com.

Copyright 2009 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved

___________________________

July 15, 2009

Joan,

Just looked at your went site and jazz lecture material on women. I am a jazz researcher writer and have written over 50 books on early Jazz. In one of my essays, I have about 20 pages on the use of women pianists in early jazz.

See my web site - www.basinstreet.com

Most early jazz bands used woman pianists as they could read. I've got to interview and know some of the pianists in the chapter. Thought I'd touch bases with you. Keep up the good work.

Karl Koenig, Ph.D.

___________________________

Dr. Koenig,

I appreciate your contacting me.

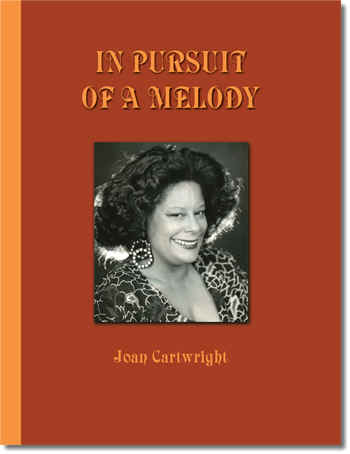

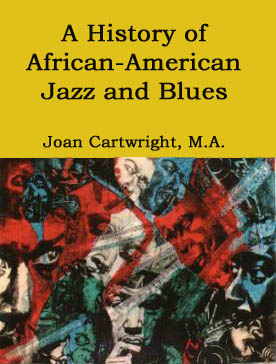

I just published my latest book, A

History of African-American Jazz and Blues.

One of the issues that I deal with addresses the problem I found in one of

your articles that reads, "Many of the song lyrics

made fun of a particular ethnic groups such as the Italians, Irish, Hebrew

and/or Negroid."

Note that even the link to your article contains the term

"negro" - http://www.basinstreet.com/articles/negrom.htm

"Negroid" is NOT a nationality. The people who made this music

were "African", a slight detail that too many Anglo historians

seem to gloss over. I don't mean to be controversial at all. I mean to

correct this indignity suffered too long by exceptionally talented people

who gave America its only true art form - blues and jazz.

I trust you understand why it is necessary for the history of jazz to be

read and written from the Afrocentric perspective. I believe my book gives

this perspective quite intelligently.

I do hope we can continue this dialogue.

Sincerely,

Joan Cartwright

_____________________

Joan,

You are a true blessing. You say what needs to be said. You do so courageously, lovingly and in truth. I am honored to be counted as one of your friends!

JH

___________________________

Hi Joan,

Yours is a worthy cause, so keep up the fight.

SM

Al Calloway

Zora

Neale Hurston’s essay, “What It Feels To Be Colored and Me” gives

a graphic account of her emotional experience with jazz.

When I sit in the drafty basement that is the New World

Cabaret with a white person, my color comes. We enter chatting about any

little nothing that we have in common and are seated by the jazz

waiters. In the abrupt way that jazz orchestras have, this one plunges

into a number. It loses no time in circumlocutions, but gets right down

to business. It constricts the thorax and splits the heart with its

tempo and narcotic harmonies. The orchestra grows rambunctious, rears on

its hind legs and attacks the tonal veil with primitive fury, rending

it, clawing it, until it breaks through to the jungle beyond. I follow

those heathen – follow them exulting. I dance wildly inside myself. I

yell within. I whoop. I shake my assegai above my head. I hurl it true

to the mark yeeooww! I am in the jungle and live in the jungle way. My

face is painted red and yellow and my body is painted blue. My pulse is

throbbing like a war drum. I want to slaughter something – give pain,

give death to what I do not know. But the piece ends. The men of the

orchestra wipe their lips and rest their fingers. I creep back slowly to

the veneer we call civilization with the last tone and find the white

friend sitting motionless in his seat, smoking calmly. “Good music they have here,” he remarks, drumming the

table with his fingers.

Hear the archived radio program hosted by Diva JC

From the

coast of West Africa captured people brought a new music to the shores of

North America. That music became blues and then jazz and was the voice of freedom. But

the commercialization of this music throughout the twentieth century has not

benefited the innovators as much as the imitators, publishers and producers

of recordings, concerts and festivals, worldwide.

The

three essays in this book by Joan Cartwright examine the cultural politics involved in the

production, promotion and critique of African-American Jazz and Blues in America

and abroad. It is available at

Diva JC

". . . transformation of jazz into a sophisticated art music . . ."??

Therein lies the problem. -- JC

Hear the archived radio program hosted by Diva JC

From the coast of West Africa captured people brought a new music to the shores of North America. That music became blues and then jazz and was the voice of freedom. But the commercialization of this music throughout the twentieth century has not benefited the innovators as much as the imitators, publishers and producers of recordings, concerts and festivals, worldwide.

The three essays in this book by Joan Cartwright examine the cultural politics involved in the production, promotion and critique of African-American Jazz and Blues in America and abroad. It is available at

Diva JC

". . . transformation of jazz into a sophisticated art music . . ."??

Therein lies the problem. -- JC